|

| Home Previous Next | |

|

|

Byrd Surface CampThursday, 7 December 2000A good friend of mine told me before I left for Byrd Surface Camp that, "the difference between an ordeal and an adventure is attitude." I guess that means I have had quite an adventure. Working in the deep field in Antarctica is a time–honored tradition. Scientists have research stations all over this continent, and a few of us get an opportunity to go out there and support them.

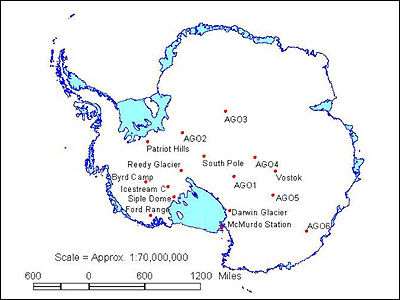

Getting out of town has been difficult. The weather this year has been most uncooperative. In fact, we are more than 50 flights behind our projected schedule for this season, and it is almost entirely due to the weather. We have broken the record snowfall for the month of November. It is amazing how much snow we have had this year. Our first meetings about going out to set up Byrd Surface Camp were about 6–8 weeks ago, and they scheduled us to leave shortly after that. The first team did not actually get out there for almost another three weeks. Byrd Surface Camp is up on the polar plateau in West Antarctica. It is at 80° south and 120° west. The land under the snow at that point is at nearly 2900 feet below sea level. The snow is a little more than 1.5 miles thick which means we were at an altitude of something more than 5,000 feet. I am told that you can add another couple of thousand feet of pressure altitude. I did experience headaches for the first day and a half which I am told was due to the altitude. Byrd Surface Camp is the more recent of several Byrd Camps in the area. The original Byrd Station was built in 1957. Within a couple of years it was entirely drifted over with snow and by 1960 it was being crushed by the snow and ice which had accumulated. New Byrd Station was built around 6 miles away. This time they cut a trench into the snow, built buildings and then steel arches (called Wonder Arches) over them. This was then covered with snow so that the station was under the surface. However, equipment vapors, human breathing and various other sources caused rime to form on the inside and over a period of several years this station was being crushed from within. In 1972 the station was redesigned and moved to the surface. It is used as a summer–only facility. When the first group arrived, the first thing they had to do was set up a radio and establish communications with McMurdo Station. They also had to put up a couple of Scott tents so that they would have shelter. Only then could the airplane leave them out there and return to McMurdo. They told me that they had terrible weather for the first two weeks — lots of wind, blowing snow and low temperatures. They built an 8–section jamesway to be used as a galley and put up individual mountain tents to live in. They had to work outside digging out the supplies and cargo left there from last year. Eleven men shoveled snow almost all day every day for two weeks. The temperatures were around –25°F with 30 mph winds. By the time I finally arrived two weeks later, most of them were sunburned, wind–burned and showed some minor signs of frostbite. When it was time for my flight to finally leave McMurdo, I was notified on Monday that I had to do a bag–drag that evening. A bag–drag means that we take all of our luggage and turn it in so that they can weigh it and pack it as cargo. I have to pack my hand–carry luggage and dress in my extreme cold weather gear as they need to know how much I weigh along with my hand–carry. I got all of my things packed and then found out everything was canceled due to bad weather. It was rescheduled for Tuesday. The bag–drag happened Tuesday evening and we were scheduled to fly on Wednesday. I woke up Wednesday morning to a very snowy day and sure enough they canceled our flight. Thursday the weather was a little better and they took us out to the runway to wait for the plane. They told us that one of the vehicles out at Byrd that was going to be used to unload the plane, was not working and that they would have to totally re–pack the plane so that we could do a cargo off–load when we arrived. So we sat at the runway for four hours. Finally they put us on the plane — a C–130 aircraft equipped with skis rather than wheels.

I no sooner got on the plane than one of the crew members asked if I wanted to ride in the cockpit for take off. Silly question. So up I went. It turns out the pilot was a friend of mine from the McMurdo Historical Society. The weather was still very bad, but they said it was all right to take off and that the weather at Byrd Surface Camp was good.

The take off and the flight were amazing. It was not long before we were above the clouds, and soon we were past the clouds. We flew across the Ross Ice Shelf (a permanent shelf of ice the size of France) and then over the polar plateau. There were no land features whatsoever. Everything was white. Occasionally you could see huge crevasse fields down below. We were flying quite high and these things still looked huge, so I cannot even imagine how big they really were.

After a couple of hours in the cockpit, I went back to the passenger area so other people could have a chance to go up front and have a look around.

Three and a half hours after taking off we finally landed at Byrd. I am very glad I was not in the cockpit when we landed, because doing the cargo off–load was quite exciting. They opened the whole back end of the aircraft as we were moving down the runway, and pushed the huge cargo pallets out onto the runway one by one.

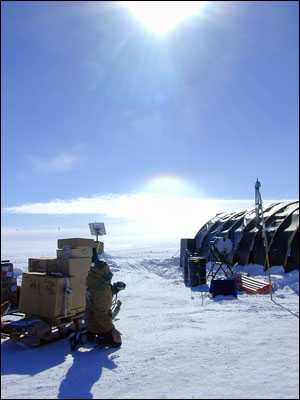

Finally the C–130 came to a stop and we disembarked. The weather at Byrd was spectacularly beautiful. As far as the eye could see, everything was very flat and very white. There were a couple of structures and a few tents about, but that was all.

The great expanse of it all was breathtakingly awe–inspiring. The vastness was amazing. The air in Antarctica is so clear that you can see so many more miles than anywhere else. It stretches on so far that you feel as if you can almost see the curvature of the earth on the horizon.

One of the amazing things to me was that, once the aircraft left us, we were just 20 people hundreds of miles from any other human beings. We were also in a place that only a few handfuls of people have ever been in the entire history of the earth. Though we had many modern conveniences by the old explorers' standards, it was very primitive by our standards. We were quite alone out there. If we were to begin walking — in any direction — we could walk several hundred miles and not see anything different or find another living creature! If we were to lose communication with McMurdo, it would be three days before they would send anyone to look for us . . . and that is only if the weather was good enough to be able to send anyone. It was a very sobering thought. The first thing I had to do upon arrival was get my tent set up. I am really glad that the weather was nice and not windy. I would have hated to be doing that in a cold and windy situation like most of the crew had done when they arrived. We had to leave quite a bit of space between buildings and between tents so that the wind would not cause the snow to build up between them. My tent ended up being the farthest one out.

As it was late in the day, we did not do any work that night. The one small jamesway that was out there was set up as a galley. One of the guys cooked a big dinner for all of us. He made steaks and onion rings and vegetables. It was great.

Cooking a dinner may sound simple, but out at a field camp it is a lot harder than I ever imagined. Our only source of water is melted snow. Many times each day someone would have to shovel a big barrel of snow and carry it inside. We would fill two pots and leave them on top of the preway to melt.

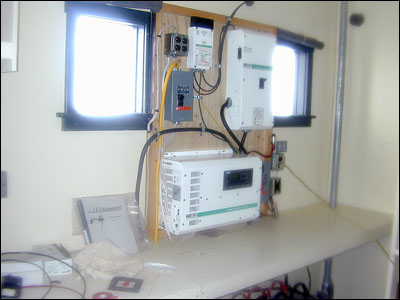

This became our drinking water, cooking water, water to wash dishes in, etc. It takes a surprisingly long time to melt all that snow, and it takes an awful lot of snow to get a little bit of water as snow is mostly air. To wash dishes we had to fill several tubs, the last being the rinse water. It is all quite an ordeal (or an adventure depending on your attitude). The next day we started working. The reason we were all out there was to help the International Trans Antarctic Scientific Expedition (ITASE) get started on their journey. What they are doing is going across Antarctica taking ice cores so that they can study weather patterns for the last 300–400 years. My job was to assist the guy putting in all of the alternative energy systems. They had several solar panels up on the roof of one of the big sleds — the one nine people were going to live in. We also put up a wind generator as a back up. Everything was tied to a whole bank of batteries inside and run through a voltage regulator.

There were several structures that they were taking on this traverse. One was the berthing unit for nine people. Another was a polar haven that is a large tent–like structure that was to be the galley and housing for three people. They had a freezer unit in which to store all the ice cores. A radar vehicle would detect crevasses to help prevent them from driving into one. This is one of the more dangerous aspects of traverses of this nature. There were two tracked vehicles — a Tucker Sno Cat and a Caterpillar Challenger — to tow the whole train of vehicles.

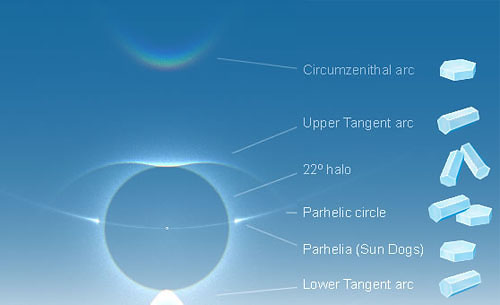

Our last full day out there was a Sunday. We had a nice breakfast before starting work. One of the carpenters was the first to go outside after breakfast. As soon as he went out he started yelling for everyone to come outside. No one stopped to put coats on as we did not know what the trouble was. We just started running. I have seen Sun Dogs (parhelions) down here before, but these sun dogs were making angles I did not know it was possible to make. There was a double ring around the sun. There were rings that were tangential to those rings. Another enormous ring bisected the sun. At the horizon was a huge white ball of light that was like another false sun. No one had a lens wide enough to capture the whole thing, much less even a large part of it. This thing covered more than half the sky. It was one of the most amazing phenomena I have ever seen down here, or anywhere else for that matter.

Here is a drawing I found online that pretty well depicts what we saw. You can find more information about it at Atmospheric Optics

We spent the remainder of the day packing up supplies on a cargo line that was set up on barrels to keep it from being totally buried in snow when the group returns.

We also cleaned and sorted out all the food in the freezer and then packed it into a new freezer. Food that was too old had to come out and get returned to McMurdo.

I found several large roasts down there as well as some frozen carrots and canned potatoes. I also found some frozen peaches. I decided it was my turn to cook dinner that night. All the guys had been working very hard and long hours for many days. So I made a big pot roast with all the vegetables cooked in it and then made a peach cobbler for desert. It was not quite as good as it would have been at home with all fresh ingredients, but it was certainly a fine meal for a field camp. Everyone seemed to appreciate it a lot.

The next day we packed up everything that had to be returned to McMurdo, including all of our waste materials. Once we knew the C–130 had taken off and was really going to arrive, we took down our tents and packed our personal gear.

While the aircraft was in the air we had to radio out weather reports every hour. Finally I looked up and saw the plane approaching the camp.

It skied in on the runway and had a picture perfect landing. They did another cargo off–load of some equipment the scientists needed.

We used the Challenger to load all of our equipment onto the aircraft. Finally we waved good–bye to the scientists and we were on our way home.

Overall I have to say that I had a truly wonderful field camp experience. I was nervous about going before I left. I was afraid of the really low temperatures, but mostly of having to sleep in a tent in that kind of weather. At least when the temperature dropped that low in McMurdo I knew I could always go inside a building and get warm. Everyone told me that I would be plenty warm in the tent, but I did not believe them. I had a very thick down sleeping bag that also had a fleece liner. The temperatures were between –40°F and –25°F. We only had one night where the winds kicked up. I have to admit that I was not only warm in that sleeping bag, but halfway through the night I was unzipping the bag and shedding clothes. By morning the tent had warmed up enough that I could dress rather leisurely and not be the least bit cold. I find it hard to believe I am saying all of this, but it was really true. Last year in my field safety training class I slept in an igloo. That was my first time ever sleeping outside. This was my first real camping trip, my first time sleeping in a tent — on the polar plateau of Antarctica! This was certainly one of the more difficult things I have ever done, but I have to say that it was also quite an adventure. |

|

| Home Previous Next | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Irma Hale McMurdo Station, Antarctica E-mail: Copyright © Irma Hale. All

Rights Reserved. Free counters provided by Vendio. |