|

| Home Previous Next | |

|

|

Wild Nights, Wildlife, and Wild IceSunday, 29 October 2000About a week ago I was out on the sea ice for one of our last sunsets of the year. As our days get longer and longer the sun travels at a very oblique path relative to the earth, so the sunset lasts for several hours. It seemed to take a very long time for the sun to finally disappear.

As the night progressed and the sunset continued,

I suddenly realized that it was not sunset any longer, but sunrise. Long before it ever got dark, the sun began coming up again.

The sun set for the last time this year on 22 October 2000 at 12:54 A.M., and rose again at 2:15 A.M. It will not dip below the horizon again until 20 February 2001. Until that time it will just circle around the sky. The night I was out on the sea ice was also a full moon. Seeing it in the rather dusky light of sunset was beautiful. The moon travels low in the sky and also at a very oblique angle. From my vantage point out on the sea ice, you could actually see the moon move horizontally across the sky as it neared Mt. Erebus and crossed over just above it.

We saw several cracks in the sea ice, but none that were too serious. And by the way, that rather small looking hill off in the distance is Mt. Erebus at over 12,000 feet high!

About 11 miles from McMurdo at Cape Evans is a hut built by the early explorer Robert Falcon Scott. The hut, with Mt. Erebus behind it and the Barne Glacier to the side, looked beautiful in the moonlight.

There was much snow around the hut and some that had blown inside as well, along with icicles and rime.

I got to spend quite a bit of time inside the hut last season, so we didn't stay long this time. Still, seeing it again was wonderful, although it was quite dark inside.

It is always amazing to see the emperor penguin on the examining table after a century.

The Barne Glacier was several miles away from where we were. They tell me that it stands between 100 and 200 feet high, so that should give you some idea of the scale.

Because the Antarctic summer is so short, most Weddell seal pups are born during a very short period of time, that being sometime in December. Even in summer the difference in temperature between the mother's womb and the world outside is around 140 degrees. And that is before the wind picks up! Even though the window of opportunity for giving birth is small, seals can mate at many different times. The females can store the sperm and when the time is right they will inseminate themselves so that the young will be born at the right time. The gestation period for seals is approximately nine months.

Occasionally, however, the timing is off and young seals are born out of season. If the weather is bad, then most will not survive. There is a colony of Weddell seals not far from McMurdo at Big Razorback Island, and some scientists have set up a camp nearby to watch them. A pup was born there about two weeks ago and so far is doing very well.

Seal milk has a very high fat content and consequently is very thick, almost the consistency of softened butter. For every pound that the young seal gains, the mother will lose two. The mother fasts during this time of suckling and in the six weeks before the pup is weaned it will have gained 200 pounds. The mother will have lost 400 pounds, and her ribs and hips will be visible. The faster the pup can gain this weight, the better its chances of survival. Norbert Wu is a wildlife photographer and film maker who is down here working on a grant from the National Science Foundation's Artists and Writers program. He has been coming here for several years and has produced many books, films, documentaries and such, as well as several articles and photographs for the National Geographic Society. A few days ago he gave a lecture on an upcoming PBS special that he is filming now. It is called Diving Under Antarctic Ice and will air as part of the PBS Nature series in 2002. He showed us some film and slides that he has taken so far this season. It is quite beautiful. Take a look at his web site. One of the helicopter pilots told me that he has been flying Norbert around so that they can do some aerial photography. The windows of the helicopter are plexiglass and they are not good to photograph through, so they took the doors off the helicopter. I can only imagine how miserably cold those trips have been. They even flew up to the top of Mt. Erebus at 12,500 feet without the doors. As the title of the upcoming show suggests, Norbert has also done quite a lot of diving down here, and photographing underwater. It seems odd to say, but that is quite a bit warmer than flying without doors. The freezing point of sea water is +28°F. That is about 60 degrees warmer than the temperatures we have been having this past week, so maybe it's not too bad. Shortly after I left Antarctica last season an enormous tabular iceberg broke off of the Ross Ice Shelf. It was 180 miles long by 25 miles wide — about the size of Jamaica — and was given the name B–15.

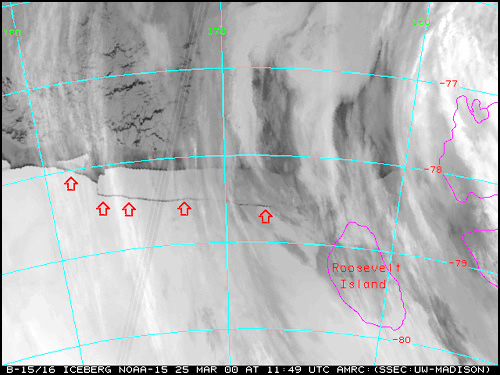

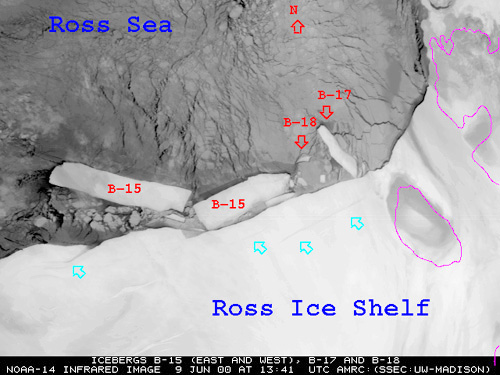

One of the scientists down here said it is the largest floating object we have ever witnessed, and he compared it to an aircraft carrier large enough to house the entire Air Force fleet. Most icebergs which break off from this area are around 1000 feet thick or more. Only ten percent of any iceberg floats above the surface. B–15 is estimated to weigh about 4 trillion tons. At some time over the Antarctica winter B–15 broke into two massive pieces.

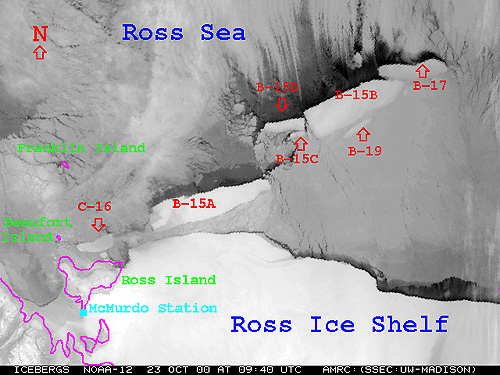

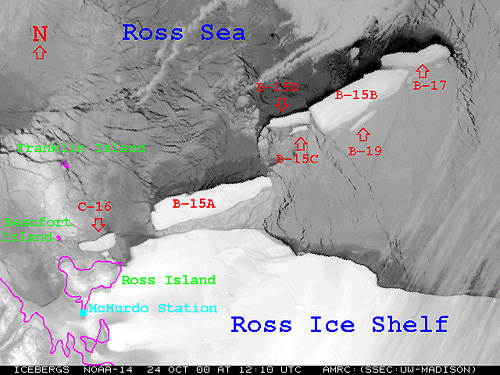

B–15 has since broken into 4 pieces: B–15A, B–15B, B–15C, and B–15D. One of these pieces, B–15A, bumped into the Ross Ice Shelf and broke off another iceberg, C–16.

Most of the icebergs which break from the Ross Ice Shelf will drift northward, however these have all stayed very close to home. The icebergs which float north will usually melt within a year, however, if they should run aground somewhere, they can be around for many years. In 1987 there was a giant iceberg which broke off the Ross Ice Shelf and ran aground south of Australia. It still survives. This current group of icebergs is slowly moving its way toward the north side of Ross Island — our home base. If any of them should make their way into McMurdo Sound, the effect on the operations of McMurdo and South Pole Stations would be massive. It would block the path of the icebreaker and the resupply vessels. That means that our annual supply of millions of gallons of heating, power, and airplane fuel, and also millions of pounds of cargo would not be able to make it in. Among that cargo is also the food and gear for the following year. Major changes would have to take place in the programs coming to McMurdo and the South Pole, probably cutting back significantly the numbers of people coming down here. Most of the local scientists still believe that the icebergs will turn north once the Ross Sea is clear of its winter ice. Fortunately they do not believe there is much chance of a worst–case scenario. It will still be interesting to watch where these icebergs go. The last photo shows the most recent position of the icebergs.

|

|

| Home Previous Next | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Irma Hale McMurdo Station, Antarctica E-mail: Copyright © Irma Hale. All

Rights Reserved. Free counters provided by Vendio. |